On 22 December last year, Mohana underwent a procedure called the ventricular septal defect closure at the SMC hospital. Under AB-PMJAY, hospitals get Rs 1.1 lakh for the procedure. Still, the family, beneficiary of AB-PMJAY, had to cough up Rs 90,000, in what was allegedly a case of double billing, or charging both the government and the patient for the same treatment.

Kewat showed ThePrint documents of the procedure that her mother underwent.

The Kewats, who barely make Rs 20,000 a month, had to partially fund the treatment by borrowing money. “We borrowed money from three to four relatives to pay the hospital and are yet to return the same since the follow-up treatment and medicine costs keep piling up,” her 58-year-old father said.

The family, however, did not formally lodge a complaint against the hospital with the state nodal agency for AB-PMJAY.

A few weeks later, in February this year, the SMC heart hospital was among 23 facilities penalised by the Chhattisgarh administration in the biggest-ever crackdown on private hospitals in the state—and possibly anywhere in the country—in a single round. The raid came based on charges of fraud under AB-PMJAY, apart from funds abuse and misuse.

The inspections at 28 private hospitals across three of Chhattisgarh’s biggest districts exposed many fraudulent practices. These included double-billing—rampant in the state—apart from fake and inflated billing, performing complex procedures when not required, showing ghost patients to raise claims, and trapping patients for unnecessary procedures through medical camps.

The raids followed inputs on fraud by the National Anti-Fraud Unit, a central agency running AB-PMJAY under the National Health Authority.

The crackdown put the spotlight on Chhattisgarh, standing out for not only the highest funds utilisation but also private hospitals’ funds misuse under AB-PMJAY.

In Chhattisgarh, a small, tribal state, the budget required to run the scheme has been steadily rising, recording a rise of over 400 percent over the last five years. However, insiders say, while the government is paying a premium for the entire state, it is mainly the urban centres, especially, in the Bilaspur and Durg districts, and the capital, Raipur, that use the benefits.

In the state, 4,000 to 5,000 daily admissions are registered under AB-PMJAY daily on average, with hospitals claiming Rs five crore per day in total.

In 2024-25, the state hospitals raised claims worth nearly Rs 2,200 crore, up from just Rs 400 crore in 2019-2020, with the private sector raising roughly 60 percent of claims, amounting to Rs 1,320 crore.

AB-PMJAY, rolled out for nearly 50 crore of the poorest Indians in 2018 to improve access to inpatient healthcare, offers over 2,000 treatment packages and covers physicians’ fees, room fees, drugs, supplies, surgeon operations, and the charges for pre-and post-operative care and intensive care.

Fraudulent activities by Chhattisgarh private hospitals under AB-PMJAY—a Modi government flagship insurance scheme—are not unique to the state.

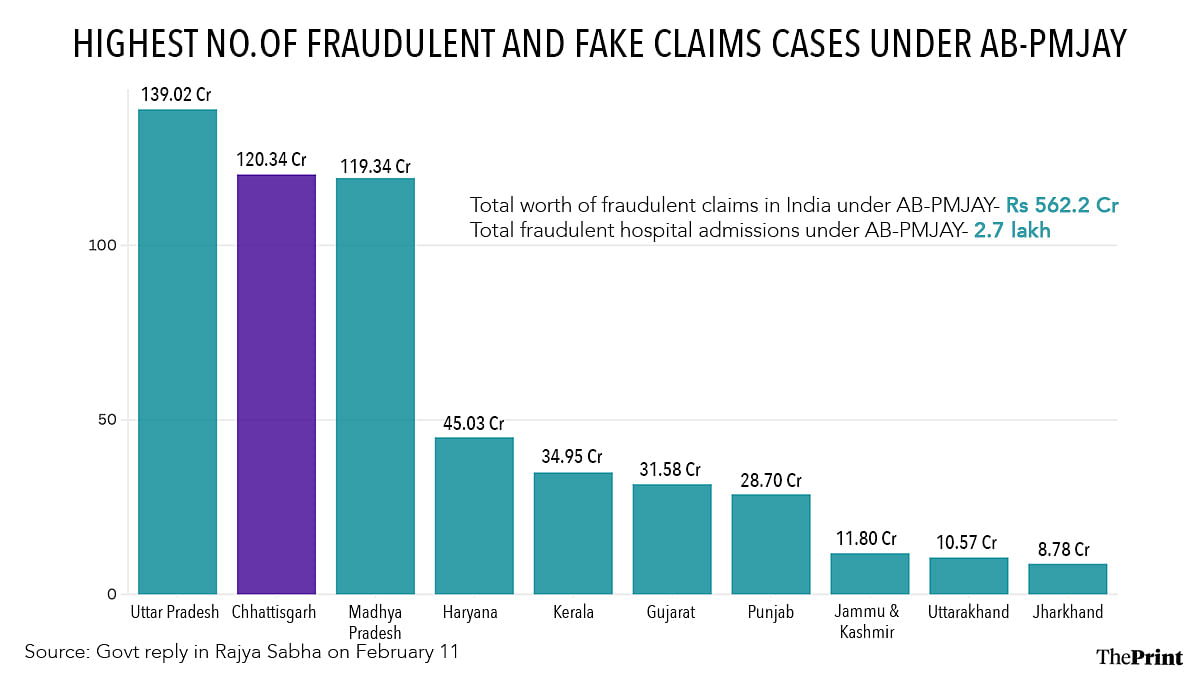

Yet, what is astonishing is its scale in Chhattisgarh, ranked 17th by population among states. From AB-PMJAY’s launch to mid-January 2025, out of fraudulent claims of Rs 562.2 crore for 2.7 lakh patient admissions nationwide, the state’s hospitals logged Rs 120 crore claims, found non-admissible later for abuse, misuse, or incorrect entries. So, at over 20 percent, Chhattisgarh recorded the second-highest fraudulent claims after only one other state, Uttar Pradesh, which raised fraudulent claims of nearly Rs 139 crore. Madhya Pradesh closely followed Chhattisgarh, raising fraudulent claims of roughly Rs 119 crore.

Responding to a query in the Rajya Sabha in February this year, the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare revealed these details in its reply.

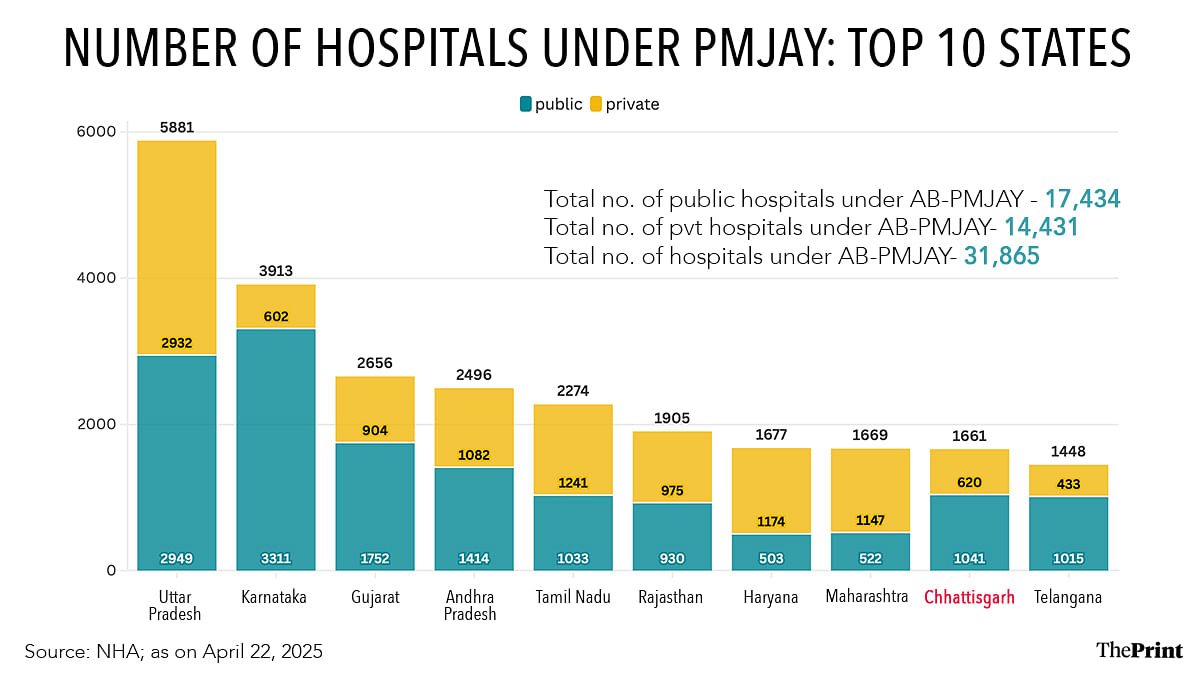

Chhattisgarh has 1,661 hospitals empanelled under AB-PMJAY—the ninth-highest number of hospitals empanelled in a state. Of that, 620 are private, according to National Health Authority (NHA) figures, whereas the state government puts the number at 584.

In neighbouring Madhya Pradesh, its parent state, which has over double the population of Chhattisgarh, 1,075 hospitals, including 578 private ones, are empanelled under AB-PMJAY. In the country, overall 31,865 hospitals, including 14,431 private ones, are empanelled under the scheme.

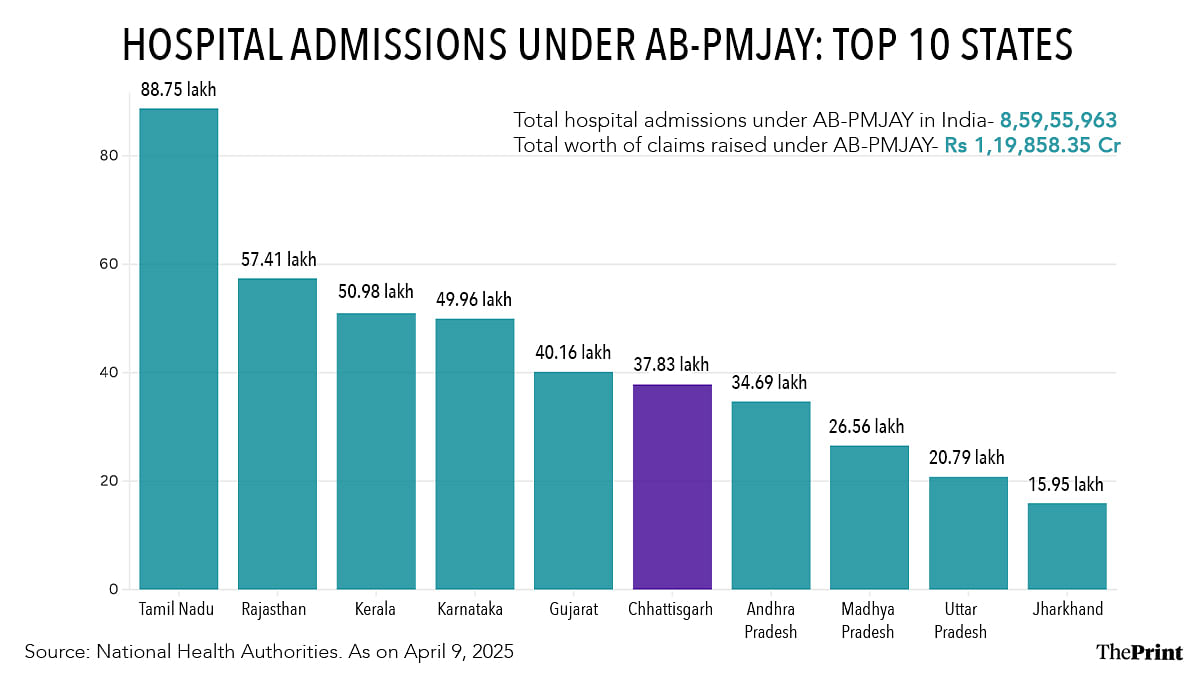

As of 9 April 2025, Chhattisgarh had registered the sixth-highest or 37.83 lakh hospital admissions under AB-PMJAY, locally known as AB-PMJAY-Shaheed Veer Narayan Singh Ayushman Swasthya Yojana. In total, there were 8.59 crore admissions across India.

The government reply in the Parliament show that Tamil Nadu, which, at 88.75 lakh, saw the highest number of admissions under the scheme, and at 1,241, also has the highest number of empanelled private hospitals after Uttar Pradesh, did not report fraudulent claim by any private players.

According to government figures, across India, 1,114 hospitals had been de-empanelled, and 549 hospitals had been suspended for three or six months.

In cases of violations of stipulated NHA guidelines, there are provisions for suspensions, black-listing, and de-empanelment of hospitals, which can also face fines and legal actions.

Of the 1,114 de-empanelled hospitals, so far, only 36 are in Chhattisgarh, despite its high share of fraudulent claims. Of those, 33 had been de-empanelled in 2024-25, the statistics accessed by ThePrint from the state health department showed.

Despite fraudulent claims worth over Rs 120 crore detected in the state, the defaulters, over the last seven years, have paid fines of only Rs 4.23 crore, with the collection highest in 2024-25, at Rs 1.27 crore.

ThePrint contacted NHA chief executive officer L.S. Changsan and the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare over emails with a detailed questionnaire on the pattern of fraud cases under AB-PMJAY in Chhattisgarh but got no response. This report will be updated if and when a reply is received.

In October 2024, when Sonmurgi Devi rushed her 65-year-old husband, Nishant Sahu, to a private hospital in Korba with a complaint of chest pain, she did not know that the hospital did not have a licence to perform angiography, angioplasty or open heart surgery, the procedure that Nishant urgently needed.

“After five days of keeping him in the ICU, I was finally referred to the government-run Advanced Cardiac Institute (ASI) in Raipur. The hospital in Korba deducted money from our Ayushman card. But the ASI doctors said his stay in Korba hospital was not required at all,” Sonmurgi Devi tells ThePrint.

Nishant underwent open heart surgery in November 2024 at ASI, but his family, too, like that of Kewat, did not lodge any complaint against the hospital in Korba for unnecessary hospitalisation.

Authorities, too, say that Chhattisgarh private hospitals have, so far, mostly had a free run, even as hospitals deny wrong-doing, accusing the government instead of delaying the release of AB-PMJAY funds for patients.

“Ayushman Bharat scheme has proved to be a boon for a state such as Chhattisgarh, which has a large tribal population … [but] it is also worrisome that the state has reported the second-highest fraudulent transactions under the scheme, and we are constantly monitoring the hospitals ….We recently took strict action against many such defaulters,” state health minister Shyam Bihari Jaiswal tells ThePrint.

The actions initiated two months ago in the state under Jaiswal have impacted some of the most well-known private healthcare providers. These include the 359-bed Raipur-based Ramkrishna Care Hospital, Agrawal and SMC hospitals in Raipur, HI-TEK and Sparsh Multi-Speciality hospitals in Bhilai, and Mark Hospital in Bilaspur.

Some under-50-bed hospitals—which logged the largest share of defrauded funds among Chhattisgarh private hospitals—also faced the music.

Documents ThePrint accessed showed that the inspecting team found evidence of gross violations of norms and wrongdoings in most cases. In some cases, the officials received bribe offers on the spot.

An office order issued by the state directorate of health services, listing de-empanelled hospitals, says that an inspection team at Durg’s SR Hospital and Research Centre, which listed 180 beds, found only 10 hospital staffers, and three patients admitted for minor illnesses, not requiring hospitalisation. The team also seized evidence of patients admitted for backache and joint pain through medical camps in nearby villages.

However, Sanjay Tiwari, the hospital owner, tells ThePrint that his hospital was unduly “targeted”. It has been a part of the AB-PMJAY network since the scheme’s launch.

“I have been raising the issue of the district administration not paying roughly Rs seven crore, claimed for when my hospital was turned into a COVID hospital in 2020-21. Now, I am being penalised for that. We have approached the high court in Bilaspur against the unfair action,” he says.

The SMC hospital in Raipur registered 44 patients under AB-PMJAY but the inspection team, on reaching there, found only 16 patients physically present. The officials also note that the hospital registered patients without authorisation, which it sought later, with false, repetitive documents.

ThePrint reached out to hospital director Dr Satish Suryavanshi but got no response. This copy will be updated if and when a reply is received.

The documents accessed by ThePrint show that the Ramkrishna Care Hospital, the state’s biggest private hospital, received 33 show-cause notices starting in 2020, mostly on charges of upcoding. Upcoding is a type of medical billing fraud when higher-level treatments than required are carried out or shown to be done to charge patients extra. The hospital was either fined, asked to return money to the patients or let off with a warning.

This February, the hospital was among those suspended for six months. It admitted nearly 30 patients under AB-PMJAY daily and offered dialysis to another 30-35. The suspension, however, was revoked in mid-April, following a written apology by the hospital.

Speaking to ThePrint last week, Dr Hardik Nilesh Bhai Shah, the chief operating officer denies any wrongdoing on the part of the hospital.

“We do not charge extra money from patients if they are eligible under AB-PMJAY, nor do we carry out unnecessary procedures on patients. There was some miscommunication during the inspection, which resulted in the suspension, but the issue has now been sorted, and the programme is running smoothly again,” Shah emphasises.

However, state health department insiders say the hospital is a habitual offender.

“It is among the hospitals against which we keep getting complaints. Hospitals like these openly indulge in dual billing and fool gullible patients by telling them they are getting huge discounts under the scheme,” a state health department official says.

At More Hospital, another private facility in the city, the inspection team found 11-year-olds with pain in limbs or other body parts wrongly hospitalised and moved to the ICU for photo ops before their shift to the general wards. On the transaction management system, app used by AB-PMJAY empanelled hospitals, the hospital showed the patients as critical. The hospital was among those de-empanelled for a year.

Senior health authorities underline that whereas registering ghost patients under AB-PMJAY was the most common fraud in smaller hospitals, dual billing and upcoding were the most common fraud cases in larger hospitals.

“We are a state where nearly 100 percent of the population is eligible for government health insurance, and AB-PMJAY covers nearly 90 percent, right now. In certain cases, medically auditing certain procedures even becomes difficult, and hospitals are taking advantage of that,” Amit Kataria, secretary of health, family welfare, and medical education department of Chhattisgarh, tells ThePrint.

In Chhattisgarh, apart from those eligible for AB-PMJAY under the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste-Census data, as stipulated by the Centre but not made public, all ration card holders are also eligible for a coverage of up to Rs 50,000 per family under AB-PMJAY-Shaheed Veer Narayan Singh Ayushman Swasthya Yojana (SVNSASY), renamed last year by the BJP government. It was earlier Dr Khoobchand Baghel Swasthya Sahayta Yojana, the name given by the Bhupesh Baghel-led government in 2023 when the Congress was in power in the state.

Whereas the Centre and state share the treatment cost burden of families eligible under AB-PMJAY in a 60:40 ratio, the state shoulders the burden for others under the SVNSASY from its coffers.

Kataria says that several hospitals go scot-free due to persistent failure to act on NAFU inputs and fewer random inspections than required by the auditing agency and third-party administrator Family Health Plan Insurance TPA Limited (FHPL) or district medical officers.

“The yearly contract of the (FHPL) agency has now ended, and we are looking to change the agency. The idea is to strengthen the medical auditing and field inspections of private hospitals empanelled under the scheme in the state,” Kataria adds.

A reason why the malpractices under the scheme seem widespread in Chhattisgarh is hospitals know they can get away with absolutely “anything”, Dr T. Sundararaman, who headed the erstwhile State Health Resource Centre, says.

When asked whether Chhattisgarh was more prone to fraud by for-profit facilities, or their scrutiny was stricter than that of government facilities, Dr T. Sundararaman, who headed the State Health Resource Centre previously, says it was a combination of both.

Published in April last year in the E, a paper by SHRC researchers based on a survey of roughly over 750 patients under treatment under AB-PMJAY in the state showed that utilisation of services under the programme involved significant medical out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) and incidence of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE)—when OOPE exceeds 40 percent of a household’s capacity to pay for healthcare. The paper noted that the medical OOPE was quite large in the case of for-profit private hospitals, and dual billing was the main culprit.

However, in October 2024, the National Human Rights Commission of India, which would advocate for the right to health and ensure access to quality healthcare for all citizens, was disbanded unceremoniously.

Raman V.R., a public health expert and one of the early leaders of health sector reforms in the state, says Chhattisgarh is one of the few states to have considered covering the entire population under a medical care financing scheme, in addition to the support provided under the CM’s special relief fund and a few other pre-existing schemes.

Eight years after the state was carved out, health insurance was introduced in Chhattisgarh in 2008 when it adopted the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY). Initially, the scheme offered inpatient benefit cover of up to Rs 30,000 annually on a family floater basis. Later, the RSBY benefit was raised to Rs 50,000. The original plan was to adopt a community-level risk pooling model alongside supply-side financing for improving health services across the state. However, the government prioritised demand-side financing via a medical insurance scheme, Raman V.R. underlines.

“When public services are provided mainly through the profit-oriented private sector, it enhances coverage of service provisions while also bringing several unethical market practices into the public service provision. This system will likely go awry when there are no proper regulations for the medical market, and corporate groups run many hospitals,” Raman V.R. adds.

Another public health researcher, previously with the erstwhile State Health Resource Centre (SHRC), a government advisory body that used to guide health policies in Chhattisgarh and monitor health schemes’ implementation, underlines that AB-PMJAY, like its predecessor RSBY, had mainly achieved one thing. The scheme had given private hospitals easy access to patients. Earlier, the facilities worked hard to trap them.

“In the absence of proper governance and regulatory mechanisms, for-profit hospitals, in particular, have made a mockery of the (AB-PMJAY) scheme and are taking advantage of the state’s funding while also exploiting gullible patients,” the researcher says on the condition of anonymity.

The researcher adds that another practice leading to widespread violations by Chhattisgarh private hospitals is the state’s lack of supervision in empanelling hospitals or reviewing them later. The NHA guidelines for hospital empanelment list various specifications, such as the number of beds, minimum services and resources required. However, the state health authorities have sweeping powers to empanel healthcare providers.

“For example, in neighbouring Madhya Pradesh, there are stricter criteria, comparatively, for hospital empanelment, with provisions such as certification from an accreditation body and a certain number of specialities. But in Chhattisgarh, hospitals are empanelled left, right, and centre, and there is no review later on,” the ex-member of SHRC says.

Agreeing with him, state health secretary Kataria tells ThePrint, “We are looking to review our hospital empanelment policy under the scheme.”

As hospitals across India complain about low package rates for health problems under AB-PMJAY, delays in payment to hospitals have emerged as a serious problem. In many cases, payment delays prompted hospitals to suspend services under the programme or deny services to patients.

In Budget 2025-26, the Union government proposed Rs 9,400 crore for the scheme—a 23.6 percent rise from the Rs 7,600.53 crore allocated in its 2024-25 revised budget. However, even the increased budget is deemed far lower than required, considering the scope of AB-PMJAY. The Centre has only extended the scope, with AB-PMJAY introduced for , irrespective of their income status, late in 2024, but complaints of inordinate delay by private hospitals persist in most states.

In Chhattisgarh, the pendency last year was Rs 3,800 crore, including the state share of roughly Rs 1,520 crore. In March this year, the state finance department allocated a budget of Rs 1,000 crore, of which Rs 1,520 crore was for the scheme.

“We have cleared a chunk of payments to private hospitals, but some pendency remains—a factor hospitals often cite when snubbed for charging patients for treatment under the scheme. We realise that we should streamline the payment process to private hospitals,” state health secretary Kataria says.

Another grievance of many hospitals, especially private ones, is that the scheme does not allow hospitals to treat patients for multiple conditions, even in medical cases, indicating such a need.

“A 70-year-old patient under treatment for a urological condition, for example, may also need treatment for a cardiac condition detected before or during the hospital stay. It is highly likely,” says Dr Kamlesh Maurya, director at Bilaspur-based Mark Hospital, which, after the February crackdown, was de-empanelled. “But since the AB-PMJAY Transaction Management System won’t allow us to enter multiple packages for any patient during a single hospitalisation, we charge patients for that, and they do not mind because there is a logic to it.”

Centrally maintained by the NHA, the statistics list haemodialysis, COVID-19 screening, acute febrile illness, a specific cataract removal procedure, and acute gastroenteritis with moderate dehydration as the top procedures availed under the scheme across India.

In Chhattisgarh, enteric fever or typhoid, which is difficult to audit medically, is among the most common conditions that private hospitals have raised claims for since 2018, right after acute gastroenteritis with severe dehydration. Then, there are the packages for vaginal deliveries, acute febrile illness and acute gastroenteritis with moderate dehydration.

“Private hospitals that repeatedly show admissions under select procedures remain on our radar. On several occasions, we alert the state nodal agency (SNA) to act on these triggers,” the top NHA official says.

A Chhattisgarh health department official underlines that in 2020-21, insurance packages for surgeries, which private hospitals commonly carry out, were removed from the AB-PMJAY list. However, enteric fever, also on the list, was back under the scheme within a year since tribal districts, in particular, are prone to report a high number of cases.

“The problem is that we have, so far, not devised any way to allow hospitals in certain districts to treat a condition endemic to that area. It means that Chhattisgarh private hospitals in other areas, including cities, might take undue advantage,” the official says.

Whereas the average claim of hospitalisation nationally is roughly Rs 13,000, it stands at Rs 10,000 approximately in Chhattisgarh.

“We understand there are some problems in the implementation of the scheme, but there are considerations underway to check unethical and fraudulent practices by private players,” state health minister Jaiswal says.

He says the measures could include making patient feedback mandatory for approval of every claim raised by a private hospital and shifting to a hybrid model of the scheme from the current trust model.

The trust model involves state-run trusts, the state health or nodal agencies, purchasing services directly from empanelled hospitals. The hybrid model combines elements of the trust and insurance models, with some claims processed by the state-run trust and some by insurance companies. “When insurance companies become a part of the process, they are likely to ensure a smaller number of unnecessary hospitalisations,” the minister says.

The NHA guidelines recommend randomly collecting patient feedback in 10 percent of procedures carried out under the scheme. However, no states have approved claims based entirely on feedback yet.

Jaiswal says that his government is keen to learn from states, such as Tamil Nadu, which appear to do better at checking fraud by private hospitals.

However, Sundararaman, current chair of the advisory committee on the CM’s comprehensive health insurance in Tamil Nadu, reckons that TN had its fair share of problems, though quite distinct from Chhattisgarh. “For example, private hospitals in Tamil Nadu deny healthcare services to many patients due to procedural issues [in implementation of AB-PMJAY],” he points out.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)