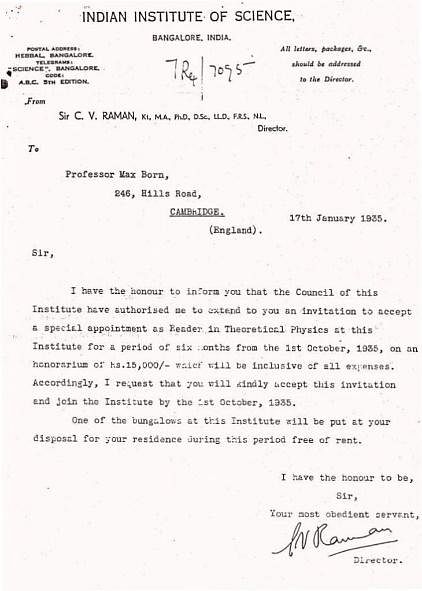

Interestingly, some of the leading academicians had even considered migrating to India in the 1930s. One such person was Max Born, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics in 1954 and was American physicist J Robert Oppenheimer’s mentor. Born spent six months during 1935-1936 at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, at the invitation of Indian physicist CV Raman.

Raman had recently moved to IISc and was keen to attract global talent to the institute. When Raman offered Born to move to Bengaluru in 1935, initially for six months and later permanently, Born had no hesitation in accepting the invitation. Indeed, Born’s six months in Bengaluru were marked by a series of lectures by him and deep academic discussions with Raman and his colleagues.

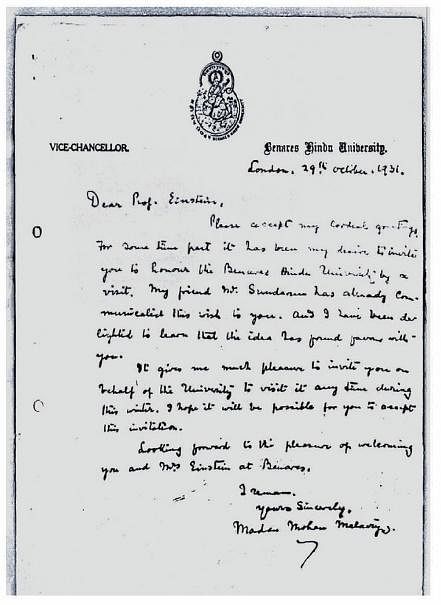

Similarly, when Pt Madan Mohan Malaviya understood the plight of intellectuals in Germany, foreseeing the immediate need to act, he offered Albert Einstein to visit the newly established Banaras Hindu University. This was in anticipation that Einstein would be pleased with the academic environment at the BHU, and eventually might be persuaded to accept a faculty position there. Both Raman and Malaviya had exceptional foresight on the contemporary situation and were willing to invite outstanding individuals to their institutions.

If the brain drain does happen now, it could undermine the US’ position as the world’s most innovation-friendly country—and as its largest economy. Independent analysts have commented on both these aspects. Consequently, countries in Europe have taken swift action on the perceived brain drain from the US. For example, the French President Emmanuel Macron has already extended an open to the best brains to relocate to France.

Is India prepared to accept a large number of talented academicians—and that too, at short notice? The situation in the 1930s was quite different than that of today. Back then, a few responsible individuals had the foresight and courage to make such decisions. Moreover, universities and institutions in India had just begun to be established, creating space and opportunity for many to find a place within them.

Despite this, Raman had faced serious hurdles in bringing Max Born on a long-term engagement. On the other hand, the academic organisations are much more mature now compared to the 1930s. The maturity has also brought unintended bureaucratic hurdles in spotting outstanding talent and offering positions in our institutions.

A new and innovative approach may be necessary if India truly wants to take advantage of the situation and attract the best global talent. The government can set up special-purpose mechanisms and rapidly implement decisions on exceptionally talented academics to return. Many newly established private universities, possibly free of the bureaucratic processes, may take the lead.

Undoubtedly, attracting such outstanding individuals, considering the current peculiar geopolitical situation, will only have a positive long-term impact on the growth of the Indian economy. Only time will tell if India seizes the opportunity or lets it slip away once again.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)