Big Bang is an exploding myth, read the sign outside his room. It was also a sort of theme song for the person inside.

For Jayant Narlikar, the established theory about how the universe came into being, through a Big Bang about 13.8 billion years ago, was never really a settled issue.

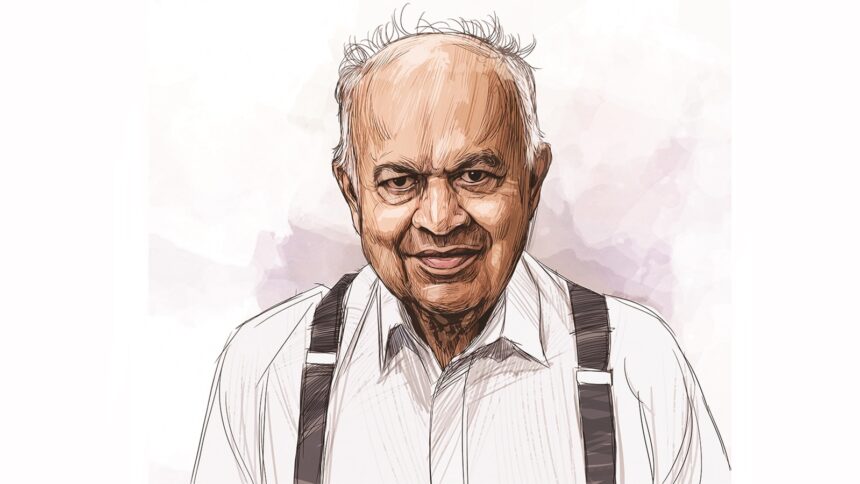

Narlikar, who had contributed immensely to the development of an alternative model of the universe along with his mentor Fred Hoyle, passed away Tuesday morning in . He was 87. Ailing for some time, he had had a fall two weeks ago and had to be operated upon last week.

One of the most celebrated Indian scientists, Narlikar, then a young researcher at Cambridge University in the UK, had attracted global recognition for his work on what is known as the steady-state theory of the universe, developed by Hoyle, in collaboration with Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold.

The Big Bang theory suggests that the universe has a definite beginning, and a possible end. In contrast, the steady state theory, which was the mainstream theory in the 1950s and 1960s, maintains that the universe has always been the way it is, without any beginning or an end.

The idea has become less popular over time, with mounting evidence that supports the Big Bang theory. But Narlikar remained unconvinced.

Acknowledging that he was in a small minority, he argued in his autobiography ‘A Tale of Four Cities’ that there was still enough evidence to “re-examine the situation”.

“It is not that Narlikar was blind to the new evidence coming out in support of Big Bang. He was a scientist of the first order. It is just that he strongly believed in his work. So, every new piece of evidence for Big Bang used to be taken as a fresh challenge by him, a new opportunity to test his ideas. And his responses, or criticism, of the new evidence used to be as scientifically rigorous as it can get,” said Somak Raychaudhuri, a former director of Pune-based Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), which Narlikar was instrumental in setting up, and where he had an office room until a couple of years ago.

“In many ways, Narlikar was like Hoyle. They had amazing ideas on several matters related to science. Many of these were very unconventional ideas, but backed by rigorous mathematics and data,” said Raychaudhuri, now vice-chancellor of Ashoka University.

The Hoyle-Narlikar theory, as it came to be known, on the steady state universe was just one such idea. In the process of formulating their model, the two also came up with an alternative theory of gravity, by modifying Einstein’s general relativity. Then there was their work on cosmological red-shifts, the fact that light coming from far-away objects appears shifted towards longer wavelengths, corresponding to the red end of the visible spectrum. Narlikar questioned the accepted understanding that the red-shifting was caused mainly by the relative motion of the source.

“Their big ideas have become out of fashion these days, but much of the underlying mathematical structures, and the methods that they developed have withstood the test of time,” Raychaudhury said.

And even, bigger ideas, including a possible alternative to Big Bang, are not completely discarded, said Ajit Kembhavi, one of the students of Narlikar, and another former director of IUCAA.

“Science is based on evidence. As new data emerge, theories evolve. Nothing is permanent. For example, there is some emerging evidence that may support newer versions of the steady-state theory. Similarly, there are many examples of anomalous red-shifts, that appear inconsistent with conventional explanations of why this happens. The scientist, Halton Arp, has been a great expert at finding these. Some of the data coming in from the James Webb Space Telescope seem to be clashing with our established theories. This is the way science advances. Alternative ideas are a must, as long as they aligned with basic scientific principles. Jayant (Narlikar) was like that,” Kembhavi said.

In his autobiography, Narlikar himself wrote that some of his ideas were probably too ahead of their time.

“One moral that I have learnt from my (and more so from Fred Hoyle’s) scientific career is that to have the maximum impact of your ideas, you must be only slightly ahead of time; if you are ahead of time by several years (as we were on this occasion), your ideas are dismissed as outlandish and then forgotten,” he wrote.

He was referring to three of his papers published in 1966, including the one on gravity, which, he said was considered “provocative” in the scientific community.

But the talks related to these papers, two years ahead of their publication, had attracted a lot of media attention, and Narlikar was interviewed by many in the UK. It got him a lot of fame back home, with even Indira Gandhi, not a Prime Minister then, sending him a congratulatory note, in which she noted that had her father been alive (Jawaharlal Nehru had passed away a fortnight earlier), he would have been thrilled by his achievements.

The international acclaim that the 26-year-old Narlikar was getting was noted by the Indian government too. Former union minister Jairam Ramesh posted a clipping Tuesday from the Yojana magazine of the erstwhile Planning Commission, an issue of July 1964, which discussed whether India should get Jayant back to the country.

Narlikar did, eventually, return to India after a few years, where he trained several generations of astrophysicists and built institutions like IUCAA.

He delved into science fiction, writing short and long stories in Marathi and English, many of which became part of the school curriculum. He pursued science popularisation, and campaigned against superstition and pseudo-science. He would specifically get himself photographed eating during eclipses to make a point. He used to organise special science sessions for schoolchildren at IUCAA and would spend hours answering their questions.

“One of his enduring legacies would be the large number of students he guided and mentored. Look at all the big names in astrophysics in India. Thanu Padmanabhan (who died in 2021), Sanjeev Dhurandhar, Ajit Kembhavi, Naresh Dhadich – all have been trained by Narlikar, and they, in turn, have trained many more. The astrophysics scene in India is quite vibrant,” said Tarun Souradeep, astrophysicist and director of -based Raman Research Institute, himself a student of Narlikar.

“Narlikar was a very good listener and very open to new ideas. It did not matter where the idea was coming from. He would often tell students, look it is amazing how that model works so well, now let us examine why our own does not work equally well in this situation. He would ask us to question established theories. Narlikar’s students excelled in very different fields within astrophysics. He never forced his own ideas on them,” Souradeep said.

In his autobiography, Narlikar made a self-assessment of his career. “Honestly, reviewing my achievements, I find that I have not done badly, although I could have done better, but at a price. Most of the awards, honours and recognitions that I have won came my way without me soliciting them. I am also aware that I could have done better on this count, if my work had supported the doctrines favoured by the majority,” he wrote.

To not be deterred by a doctrine just because it is favoured by the majority is what his life was about – both its art and its science.