What have both sides achieved and lost? To answer this question, I examine the political and military aims of the rivals, their execution strategy, and the results.

India and Pakistan traditionally do not formally state their political/military aims and execution strategy. However, based on the unfolding of events, I have deduced these in terms of military theory.

India’s political aim was to reimpose its deterrent on Pakistan to prevent it from perpetrating a terrorism–driven proxy war in Jammu and Kashmir, and similar action anywhere in the hinterland. This was to be achieved through military operations below the threshold of a limited war and Pakistan’s nuclear threshold.

India’s military aim was to conduct controlled escalatory (action-response-action) military operations without physically violating Pakistan’s ground and air space to impose a psychological defeat by creating conditions that made the enemy’s response cost–prohibitive.

The above strategy was to be executed primarily by the IAF, relying on its marginally qualitative but substantially quantitative superiority to selectively destroy terrorist and military targets in Pakistan from within Indian territory. The Army’s air defence and unmanned aerial systems (UAS) would supplement the IAF’s resources. The Indian Army and the Indian Navy were to adopt a strategic defensive posture and maintain a high state of readiness to switch to the offensive as a contingency. The initiative was to be seized and retained from the word go. Knowing the adversary’s panache for quid pro quo plus, severe cost was to be imposed on every response and raise the level of escalation until the cost became too high for Pakistan to sustain.

Pakistan’s political and military strategy are both decided by its armed forces. Its political strategy was to prevent India from reimposing its deterrent with a decisive victory, and retain its strategic autonomy. In doing so, it was hoping to make itself relevant in the international arena and also bring the Jammu and Kashmir “dispute” back into focus.

Its strategy was to stalemate India through innovative exploitation of its limited high–end military technology, defeat India’s escalatory offensive military operations, and launch a riposte of higher intensity to make further operations cost-prohibitive. In the event of unacceptable losses, nuclear brinkmanship would be commenced to invoke international pressure on India. As the weaker adversary, Pakistan did not want to initiate the conflict. Its military strategy was, to a large extent, influenced by the 2019 Balakot experience with Operation Swift Retort. Like India, Pakistan also decided to keep its relatively weaker army and navy on the defensive.

With near parity and both sides adopting a similar strategy, the outcome of the conflict lay in the psychological domain by forcing the adversary to blink.

India took the initiative, targeting nine terrorism hubs in Pakistan, including Muzaffarabad in POK and Muridke and Bahawalpur in Punjab, from 0105 hours to 0130 hours. The IAF used air-to-ground missiles, flying 50-60 km within Indian airspace. Possibly, some drones of the IAF/Army were also used. These terrorism hubs were the command, control, ideological, and training centres for the proxy war in J&K and some also served as launch pads for infiltration.

All Indian strikes were successful, and credible proof was provided later of the destruction of critical infrastructure. In all likelihood, these hubs had been thinned out in anticipation. However, India claims to have killed 100 terrorists, including some prominent terrorists guilty of major attacks in India—as was evident by the attendance of Pakistani politicians and senior officers at their funerals. In tune with New Delhi’s political and military aims, the strikes were symbolic, targeting international perception and the domestic audience, which demanded retribution.

Pakistan had anticipated this action and had planned to aggressively seize back the initiative. As per my assessment, 125 fighter aircraft—85 of India and 40 of Pakistan—were in the air along with airborne warning, electronic warfare, and control aircraft operating in the depth. State-of-the-art long-range air defence systems—Pakistan’s HQ-9 and India’s S–400—were deployed 70-100 km from the border, and still had a residual range of up to 150-200 km across the border. In order to maintain surprise, the IAF had not carried out any SEAD (Suppression of Enemy Air Defence) operations in advance or simultaneously. Also, the IAF probably expected the primary response of the PAF to be with fighter aircraft. are a prerequisite for any offensive air action, and avoiding them turned out to be a costly error of judgement.

The air battle lasted for over one hour. PAF fighters remained in depth and carried out engagement at maximum ranges, hence the relative ineffectiveness of Pakistan’s air-to-air missiles. The IAF’s air-to-air engagements probably met a similar fate. Misinformation and disinformation will keep the results of air to air battle in the realm of speculation.

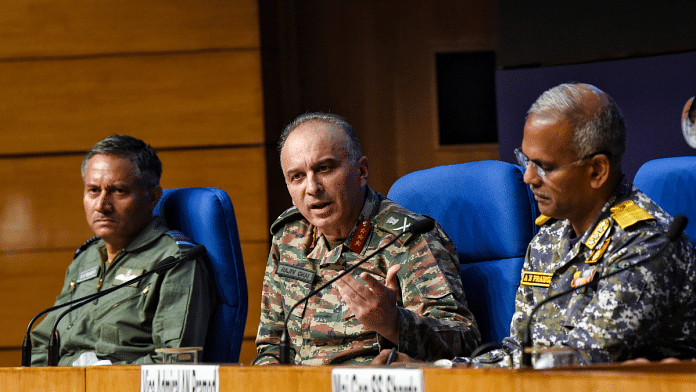

The IAF’s air packages were operating relatively closer to the border, to give the enemy air defence less time to intercept the air-to-ground missiles. As a result, they came in the range of Pakistan’s HQ-9 air defence system. The same was true for the PAF fighters coming in the much longer range of the S-400. It’s evident that IAF had some losses in the air, as indicated by Air Marshal AK Bharti in the tri-services briefing. He also claimed that the IAF had shot down an unspecified number of PAF planes.

It is my assessment based on open sources, that both sides lost a few aircraft primarily due to air defence. Results of air-to-air engagement are speculative due to targeting at and beyond maximum ranges. I have omitted the actual figures for security reasons.

As a result of this air battle, both air forces either went into the hardened pens or remained out of engagement range for the next 72 hours. The focus of both sides shifted to suppression of enemy air defence. Successful targeting of terrorist hubs notwithstanding, in my view, the air battle ended in a stalemate.

With its tail up and wanting to take the battle to Indian territory, the PAF and Pakistan Army began probing India’s air defence assets with drones on the night of 7 May. Little or no damage took place and India’s air defence remained effective. The IAF by targeting enemy air defence with Israeli Harpy and Harop UAS. One major radar and one air defence system were destroyed.

Over the next two nights, Pakistan put its entire drone fleet into battle. In total, 36 locations were targeted on the night of 8 May, and 26 on the night of 9 May, from Leh in the North to Sir Creek in the South. As per India’s military spokesperson, Pakistan used of all hues to target air defence systems, radars, forward airfields, and ammunition dumps. The psychological impact of screaming sirens, drones coming in waves, and tracers of air defence weapons lighting the sky was phenomenal, as was evident in national television’s live telecasts. As per my assessment, about 100-125 of these drones were armed, medium-range-long-endurance UAS procured from China and Turkey. The rest were likely low–end rudimentary drones, used to create a psychological impact, locate air defence systems, and make them waste their ammunition. Pakistan also used some tactical ground–launched rockets and missiles.

India’s Integrated Air Defence Command and Control System and air defence weapons proved their worth. Most of the drones and missiles were neutralised with electronic warfare or destroyed by air defence/composite anti–UAS system. Home–made Barak 8 and Akash systems also proved their worth, along with shoulder–fired Igla MANPAD. Older systems like IAF’s Pechora and Army’s L-70 guns and Schilika/Osa-AK systems also performed well. The drones that got through did not cause any substantial damage due a lack of accuracy and the incompetence of ground controllers.

Clearly, India’s air defence got the better of the Pakistani drones. The enemy’s drone attacks, over three consecutive nights, performed well below expectations. The IAF successfully responded with its drones at a limited but more effective scale due to better technology and tactics. Pakistan’s mass use of drones should ring warning bells. Imagine if these drones were handled by a more competent adversary. Indian Armed Forces must adopt drone warfare in letter and spirit.

Round 2 of the conflict went to India’s air defence.

On night of 9 May, Pakistan launched a number of long–range missiles at our airfields. Some of these missiles failed and others were intercepted.

By this time, the IAF had evolved effective counter–measures against Pakistan’s long–range air defence and air-to-air capability of its fighters. India also decided to go up the escalation ladder. In the early hours of 10 May, in a spectacular display of its prowess, the IAF eight major airfields and four radar sites/defence installations with air-to-ground missiles like BrahMos and SCALP. All the targets were hit, and verifiable proof was provided. Neither Pakistan’s air defence nor its much–touted fighters could interfere with this operation. Pakistan failed to retaliate to these strikes for fear of losing its valuable, limited assets.

In tune with the political and military aims, the scope of the strikes was limited to a show of prowess and avoided causing large scale destruction. There is speculation that the IAF hit a nuclear weapons storage site at Kirana Hills near Sargodha—by design or default. We may never know the truth, but the speculation lays bare the helplessness of Pakistan’s military.

In 75 hours, the IAF ruled the subcontinental skies. A ceasefire being sought was only a matter of time.

Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu famously said: “To win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the acme of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” Borders were not physically violated, the use of force was controlled at each level of escalation, and the enemy’s armed forces are still virtually intact. Yet, India has imposed a crushing psychological defeat on Pakistan. It has reimposed its deterrent and achieved its political and military aims in totality. There is much talk about Pakistan becoming relevant and hyphenated with India, and the Kashmir issue being internationalised. This is a peripheral issue, keeping in view India’s rapidly rising comprehensive national power.

Let there be no doubt that the notwithstanding, this deterrent can only be sustained by maintaining an overwhelming technological and military edge, which must be economically out of reach of Pakistan. With near–technological parity, the armed forces have delivered this recent victory by the skin of their teeth. Indian Armed Forces need to be transformed, and this requires political focus. It’s crucial that the defence budget is doubled to 4 per cent of the GDP.

My salute to the armed forces—it was their finest hour since 1971.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)