DAYS AFTER India notified Pakistan that it was placing the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance with “immediate effect” following the Pahalgam terror attack, Islamabad has — for the first time — signalled its willingness to discuss Delhi’s concerns about the treaty, The Indian Express has learned.

Pakistan’s Water Resources Secretary, Syed Ali Murtaza, is understood to have recently responded to India’s formal intimation of the Union Cabinet’s decision to keep the treaty in abeyance, and offered to, on behalf of his government, discuss the specific terms India objects to.

Sources aware of the development said, Murtaza, however, questioned the basis of the decision, pointing out that the treaty itself did not have any exit clause.

Murtaza’s offer to discuss India’s objections is especially significant because despite two prior notices — in January 2023 and again in September 2024 —requesting a “review and modification” of the IWT, Pakistan had not expressed its explicit willingness so far. It is only after India placed the treaty in abeyance with immediate effect after the April 22 terrorist attack in Pahalgam, that Pakistan seems to have signalled its willingness.

called Murtaza’s office on Wednesday but did not hear back.

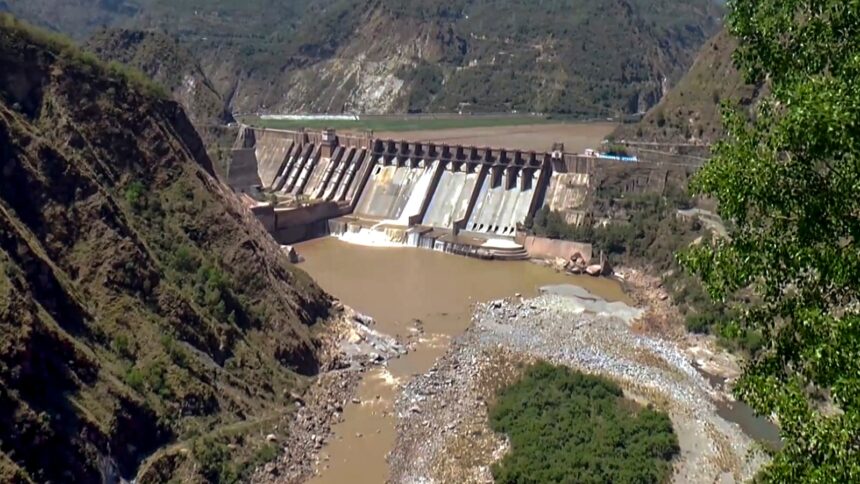

Pakistan’s willingness to engage on the Indus Waters Treaty is being discussed within the government now that hostilities have paused after four days of military confrontation. India is keen to utilise the water in the river, by building dams and reservoirs to store water, and utilise it for power generation too. Islamabad’s engagement is aimed at stalling such plans, since any construction would change the status quo on the ground.

Murtaza’s missive was in response to his counterpart Debashree Mukherjee’s letter of April 24, two days after the Pahalgam attack. “The obligation to honour a treaty in good faith is fundamental to a treaty. However, what we have seen instead is sustained cross border terrorism by Pakistan targeting the Indian Union Territory of and Kashmir,” Mukherjee wrote.

“The resulting security uncertainties have directly impeded India’s full utilisation of its rights under the Treaty. Furthermore, apart from other breaches committed by it, Pakistan has refused to respond to India’s request to enter into negotiations as envisaged under the Treaty and is thus in breach of the Treaty. The Government of India has hereby decided that the Indus Waters Treaty 1960 will be held in abeyance with immediate effect,” she further wrote in her letter.

Since then, Operation Sindoor, a counter-strike launched by India hitting terror sites in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Pakistan, and air bases in the country, has come to a pause after the two countries agreed to cease all military action by land, air and sea from 5 p.m. on May 10. But New has remained firm on maintaining all coercive diplomatic measures, the most important being the suspension of the IWT.

On Tuesday, MEA spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal reiterated this stance, saying, “The Indus Waters Treaty was concluded in the spirit of goodwill and friendship, as specified in the preamble of the treaty… India will keep the treaty in abeyance until Pakistan credibly and irrevocably abjures its support for cross-border terrorism. Please also note that climate change, demographic shifts and technological changes have created new realities on the ground as well.”

This aligns with Prime Minister ’s first message to the nation after Operation Sindoor, in which he signalled his intention to keep the treaty suspended by saying, “water and blood cannot flow together”.

It is understood that if and when negotiations begin on modifications to the treaty, India will insist that these be a completely bilateral exercise with no involvement of any third party. Accordingly, it is unlikely that India would agree to the World Bank’s — or anyone else’s — assistance in brokering revisions.

Among the clauses that India is keen to modify is the dispute-resolution mechanism under the IWT. Currently, both countries and the World Bank seem to have different understanding or interpretation of how treaty disputes should be resolved. India would like this to be laid out in black and white — preferably as a graded resolution system — rather than having two forums (a court of arbitration and a neutral expert) address the same issue, as has happened with the Kishanganga and Ratle hydroelectric projects.

The Indus Waters Treaty was signed on September 19, 1960, after nine years of negotiations between India and Pakistan. It has 12 Articles and eight Annexures (from A to H). As per its provisions, all the water of the “Eastern Rivers” — Sutlej, Beas and Ravi — shall be available for the “unrestricted use” of India; Pakistan, meanwhile, shall receive water from the “Western Rivers” — Indus, Jhelum and Chenab.